Now we are on to the arching. I was going to do the cross arches first but I don't have the curves drawn up, so I'll start with the more controversial long arch. Controversy on a design 400 years old? Yes. Almost every facet of violin making has more than one way of accomplishment. From grounds and varnish, to inside arches and outside arches, there are camps divided, and pitted against each other holding their views close to their hearts, and in secret if need be. I take the pragmatic approach...I do what seems to work.

Whereas the outside cross arch is, for the most part, deemed to be something close to a curdate cycloid, the long arch isn't. A curdate cycloid is the curve you get when you roll the wheel of a Spirograph along the straight gear. Some like to say the long arch is a cycloid at the ends. Others insist they are circles. I use two different, but related forms, one for the belly, another for the back.

Let's start with the belly. There was an article in the Stad magazine a couple years back that confirmed an idea, or at least made me a little less uneasy knowing I wasn't the only one thinking that way, that the inside of the belly arch was a catenary curve. A catenary curve is the curve a chain forms when held at each end and left to naturally fall in the middle. But it isn't just a simple catenary. The ends of the violin body are only carved on the inside up to the end blocks. If you draw a line straight across form the end blocks to about 10-25mm from the edge of the plate you will end up with the top line shorter, again by a simple ratio, than the bottom line. The catenary curve goes on a diagonal from the ends of the lines by the blocks. Where the lines converge is above the centerline of the violin. The cross arch on the inside is a catenary as well and they are carved in to blend with the diagonal arch. The affect of this is to make the curve on the centerline of to belly deepest at around the bridge line. Over years the violin will get pushed down at that point from the string pressure and will bulge slightly at the bouts from the ends being pushed in. The outside curve that results from adding the belly thickness is an ellipse, that is slightly higher near the bridge. So it isn't really an ellipse, but is very close.

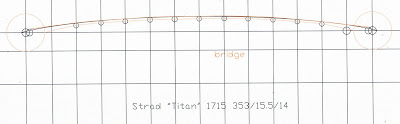

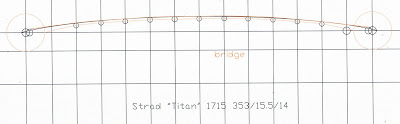

The black line on the drawing is an ellipse. Red is the outside arch and orange is the inside arch.